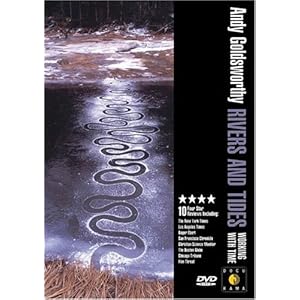

This week I watched “Rivers and Tides,” a wonderful film directed by Thomas Riedelsheimer, about the art of Andy Goldsworthy. Goldsworthy works outdoors, often in the Scottish countryside where he lives. He uses elements from the natural world—leaves, stones, moss, bracken, ice—in surprising ways to create beautiful and powerful forms.

Much of his work endures only for a few hours, or even minutes, undone by elements as natural as the materials he uses. He brings to his work the expectation that it will soon yield to water, heat, gravity, wind, growth, decay, and time, incorporating nature’s claim on his creations into the viewer’s experience of the art. His ephemeral art, made of elements yielded by that particular place, are offered back to the landscape. Nature reclaims the elements of his work and once again changes their form. He says of a serpentine line of ice, made from icicle fragments and glowing gold in the rising sun, “The very thing that brings the work to life is the thing that will cause its death,” as the sculpture begins to melt.

In one sequence (you can view a clip here) he uses bleached driftwood to build a beautiful, domed structure with a perfectly round hole in the top, like the oculus of the Pantheon in Rome. He constructs it at a place where river and sea meet, the lines of the rounded walls echoing the swirling motion of the water next to it. As the tide comes in, the water washes up around the dome and lifts a few of the logs at its base. They separate from the structure, encircling it and becoming part of the circular flow mirrored by the lines of the dome. As it yields to the water, the dome becomes an even clearer expression of the motion it is made to suggest.

As Goldsworthy says in the film, “It doesn’t feel at all like destruction.” Eventually it is carried away by that very motion and incorporated into a flow it could only emulate when it was intact. He could be speaking of this circular structure later in the film when he says of another piece, “The sea has taken the work and made more of it than I ever could have hoped.”

Watching this film, I could feel my heartbeat slow, my breathing deepen, my muscles relax. When it ended, I felt the kind of inner quiet and spaciousness that comes after prayer or meditation. A sense of reverence infuses the film. It evokes a sense of wonder and of awe.

Goldsworthy’s rooted presence in the natural world, and his ability to convey it through his work and his words, are a rare gift. He brings deep attention to growth and change in nature, to the details of creation. He knows the characteristics of rocks and leaves, the path of the river, the ebb and flow of the tide. He seems to be exploring how to live in relationship with the overwhelming power of the natural world, finding ways to meet it with his own power as an artist, and working to know the world around him and his place in it.

His work is a reminder that we are part of a miraculous creation, in its enormity and power as well as its specificity and detail. Living with the kind of attention he brings helps us to be present for moments of divine clarity, when life on this earth shimmers with the presence of a reality beyond the one we can know.

What helps foster a sense of reverence in your life?