We’re approaching Epiphany on January 6—the twelfth day of Christmas, or “old Christmas” to some. I hear the word epiphany used mostly in the context of literature, probably because real-life epiphanies are rare. It means a flash of insight, a sudden revelation about the true nature of things. Something happens that triggers a new way of seeing things, a new level of understanding. A perspective that was previously unattainable suddenly becomes the new reality.

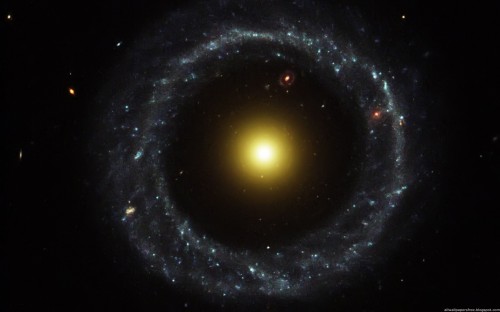

Epiphany as a holiday, or holy day, recalls the story of the Magi from the East who, in seeing a new star at its rising, discerned that a very special child was born. The child’s star was such a powerful sign it moved them to set out on a long journey, following the star as it led them to see for themselves the hope that had come into the world. When the star stopped over the place where the child was, they were filled with joy. They entered the house and saw him with his mother, Mary, then knelt before him. Their appearance honored his singular fate as they offered him precious gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh.

Who couldn’t use an epiphany? We stand in need of a higher mind, a broader perspective. Or at least an idea we haven’t thought of before. Both individually and collectively, we live with conflict that seems irresolvable. One worthwhile goal can undermine another. Resources are limited but needs go on and on. The realities of life don’t fit together in a way that makes sense. How can a king be born in a stable? How can one who dies on a cross be a savior?

Carl Jung taught that learning to live in the dualities that life deals us is how we grow. We’re pressed to develop a broader view that somehow encompasses both. But there’s nothing comfortable about it. When we can acknowledge the individual value of those things that exist in tension, rather than rejecting one or the other out of hand, there are no simple answers. But in living with that complexity, rather than forcing an artificial simplicity, we become better, deeper, more thoughtful, more compassionate people.

As we move toward Epiphany, and into the new year, what kind of guiding star are we following? What is the vision that calls us to lift our gaze upward, above the daily routines, to cross the desert and move toward hope? What do we need to see for ourselves that will give life meaning? These questions aren’t easy, either. But in asking them perhaps we invite the possibility of Epiphany.