A strong thunderstorm blew through the neighborhood a few days ago. It felled a massive maple tree that had offered shade on my regular walking route for years. But I’m just a newcomer. That maple had been part of the landscape for generations.

The huge tree seemed solid and enduring. The strength and stability amassed during all its years of growth appeared unassailable. But the power of the storm revealed otherwise. Its heartwood was rotten, and the appearance of strength belied the tree’s ill health.

The house beneath the tree was spared, fortunately, because of the direction of the wind. When the trunk splintered several feet above ground, it fell toward the street. Had it toppled in the other direction it would have crashed through the roof.

Now that the broken remains of the trunk are exposed to the light, it’s easy to see that the tree should have been removed years ago. But it would have been difficult to muster the will to remove such a magnificent presence. The branches offered welcome shade in the summer and glorious foliage in the fall. There must have been signs that the tree was unhealthy, though I certainly didn’t notice. It’s easy to let such things go for another week, another season, another year. Surely it will be ok a little longer. Until it isn’t.

Was it unimaginable that such a tree would violently break? Certainly not, though apparently the owner of the property didn’t see this coming. Or didn’t want to.

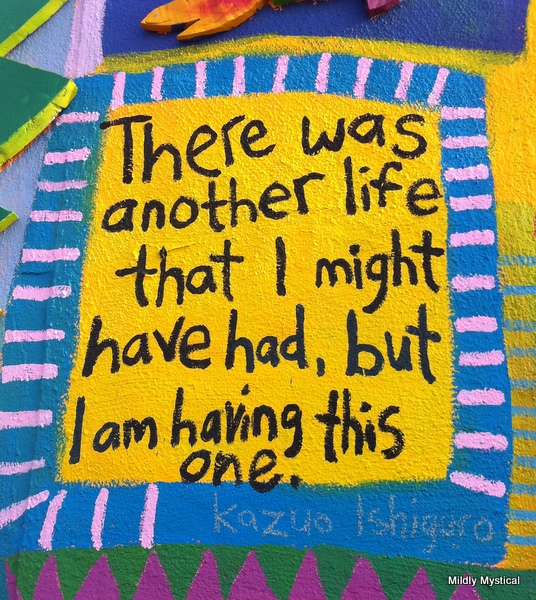

One of our most powerful resources is our attention. Where we direct our attention influences how we use our energy. “Where attention goes, energy flows.” What we pay attention to, and what we ignore, shapes our lives. We can choose what we will attend to, or allow our attention to be directed by longtime habits of thought, emotion, and behavior, along with the urgencies of daily life.

Internally, the things we habitually focus on (and ignore) compel us to keep repeating the same old patterns. Externally, all kinds of voices clamor for a foothold in our minds. Our wiser self knows what we need to pay attention to, but it takes real effort to hold on to that awareness. We need some kind of daily practice to stay connected to what our best self knows.

When we’re not paying attention to our lives, we miss what’s really going on. We overlook the new growth asking to be cultivated, and ignore the danger of familiar but rotten practices whose time is finished.

In order to be present to our lives we must be present to ourselves. There is no clarity about what’s happening in our interactions with others or in the events of our days unless we’re also aware of what’s going on within. Attending to our inner self allows us to see more clearly and respond more effectively to what’s happening in the world. It makes us less susceptible to manipulation, and frees us from the patterns that confine us.

Life is all about change. It’s easy to miss those changes unless we can be fully present, receptive to what’s really going on. Bringing our attention to what’s happening in this moment, rather than getting caught in our familiar thoughts and emotions, allows us to see what’s in front of us more clearly.

Maybe there’s something we need to do differently. Maybe there are aspects of how we live that were once solid but now need to be removed. Showing up fully, with the courage to pay attention, is an act of love. It’s when we’re truly present that we can perceive accurately, respond appropriately, and do what needs to be done.

Susan Christerson Brown