Over the past few weeks my Mystics Reading Group has been discussing Brother Lawrence of the Resurrection’s Practice of the Presence. Brought to new life by Carmen Acevedo Butcher’s recent translation, Brother Lawrence has become my teacher.

Brother Lawrence lived in 17th century France. He took monastic vows after serving as a soldier in Europe’s horrific Thirty Years War, in which he suffered emotional trauma along with a leg wound that never healed.

Life had shown him how little control he had over his circumstances. His duties in the monastery were hard work and he learned to rely on God’s help to get through the day. As 12-step spirituality teaches today, Brother Lawrence recognized that he was powerless to make his life ok.

Neither did he have to power to change the harsh political and economic realities of his time. He had seen human beings’ capacity for violence and cruelty; new instances of injustice did not shock him. Rather, he was surprised that the state of the world wasn’t worse. He prayed for the perpetrators and left the task of changing them to God.

What a counter-cultural approach! Embracing powerlessness is anathema in our culture. Experience argues that if the good guys don’t try to wield some kind of power then the bad guys win; if we want to make a difference we have to be in the arena; we have a responsibility to engage in the struggle. And if we don’t have the power to actually change things, we can at least harness our anger and name what needs to be changed.

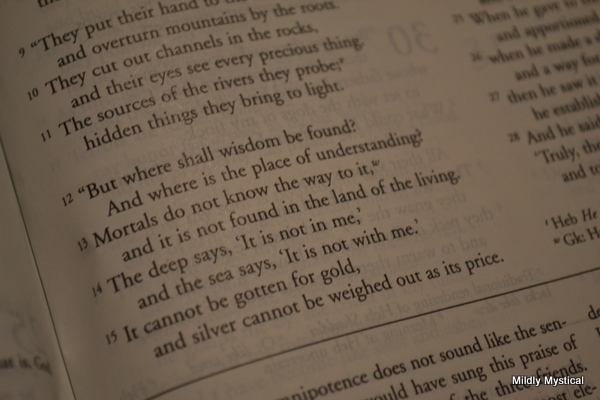

If we believe this, then what good does it do to simply live a more peaceful, joyful, and loving life? How does an individual’s state of mind, or state of grace, make any difference to the pressing questions of the day? How does one simple monk far from the rooms where power is negotiated, or the fields where power is taken by force, affect anything?

Yet almost 400 years later, it is Brother Lawrence’s words we’re reading. The wars and the fortunes of his time came to an end, but his teachings remain. His example of not resisting the things imposed on him, while trusting that Love would sustain him through it, is like the discovery of a rejuvenating spring of water available for us to drink.

In the midst of hardship, he found a Source of divine love unfailingly accessible within his own being. And as he practiced remembering and reconnecting with this Presence throughout the day, he found himself bolstered by a flow of love and power beyond anything of his making. Life became joyful, filled with meaning, beauty, and love.

As Brother Lawrence became grounded in Love, he made peace with all that he could not control. His circumstances no longer had power over him. Yet he was anything but passive. His practice of Presence set him free to act from a place of greater wisdom. When he stopped trying to control or resist what he was powerless to change, he unleashed the transformational nature of his own agency.

We generally don’t want to consider how little power we have, whether it’s over our personal lives or over the national and global realities reported in the news. We torment ourselves over how to play a part in the power struggles of our time. All the while, our engagement with issues of power distracts us from recognizing our unlimited agency.

We can decide where our attention and energy will go. We can seek the highest use of the unlimited agency that we do have, and discern the most life-giving use of our limited ability to act. And in making these choices we can be guided by the inner light that is our inheritance.

I’m not strong enough, smart enough, well-connected or well-informed enough, to know how to fix what’s wrong with the world. But if I’m open to it, I’m shown the next thing I need to know and the next thing I need to do. It shows up as something new, something I didn’t think up, something I didn’t know before.

I want to live out of this balance of humility and responsibility, seeing clearly the scope and limits of my power, along with the best use of my agency. I want to let go of wasting my energy on what I cannot change, while being open to guidance about what is mine to do.

May we all apply what Brother Lawrence teaches about the Practice of the Presence. May we bring light into our place in the world, with the courage to receive what Wisdom shows us, and the strength to act upon it.

Susan Christerson Brown