“Hope is a choice that becomes a practice that becomes a spiritual muscle memory.”

Krista Tippett offers these words of wisdom as she introduces the final, soaring section entitled “Hope,” in her new book, Becoming Wise: An Inquiry into the Mystery and Art of Living. I see three aspects of her conversations with others about hope that apply directly to the cultural climate of our nation: resiliency, relationship, and how we go about looking at the world.

Tippett talks about resiliency as she considers where hope comes from and what fosters an attitude of hopefulness. Resilience contains the expectation of adversity. People who are resilient have been through difficulties, and know from experience that hardship will not defeat them. Their resilience is a fundamental aspect of their hope. It provides perspective and helps guard against cynicism and despair.

One of Tippett’s conversation partners is Brené Brown, whose research into the values and practices of people who live wholeheartedly are reshaping our ideas about strength and relationship. There is nothing mushy about how Brown understands hope. “Hope is a cognitive, behavioral process we learn when we experience adversity, when we have relationships that are trustworthy, when people have faith in our ability to get out of a jam.” In other words, resilience learned from experience, combined with a sense of community and the power of co-operative effort, give rise to hope.

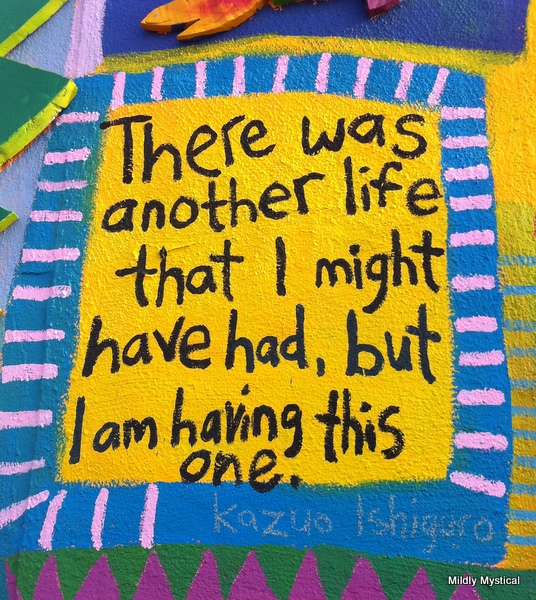

Maria Popova is the force behind Brain Pickings, a wise and enlivening presence on the web. Her conversation with Tippett brings another key aspect to considering the source of hopefulness. Popova recalls William James saying “My experience is what I agree to attend to, and only those things which I notice shape my mind.” James’s observation has everything to do with how we see the world. We see what we are prepared to see. Popova goes on to say, “And so in choosing how we are in the world, we shape our experience of that world, our contribution to it. We shape our world…”

With this election season upon us, our nation has a specific context in which the commitment to hope matters. Resiliency, working together, and the ability to see clearly are needed for the future of our democracy.

Hope is not naïve optimism or myopic quietism. As Tippett states, in “the deaths of what we thought we knew” there is a possibility of rebirth. We can get to a better place together if we can remain courageous and “let our truest, hardest questions rise up in our midst.” Asking the hard questions that arise during hard times, with the humility that allows us “a readiness to see goodness and to be surprised,” is a way to move forward.

We must vote for our nation in this coming election. We must vote for the opportunity to work on problems together. We cannot allow despair to overthrow our ideals of shared government in favor of despotic anger and cynicism. We cannot fall for the dark illusion that “they,” whomever “they” may be, are responsible for all that is wrong. We must ask for clear-eyed vision, and work on the truest, hardest questions together.

There is only one responsible candidate for president in this election. If you can’t vote for Hillary, then consider it a vote against Donald Trump. Vote for the constitution, for our nation, and for the chance to work out our problems in a responsible way. Consider the practice of cultivating hope, not hate, and then vote with your heart.

And in case you missed it, consider this powerful message from Disciples minister, Rev. William Barber.