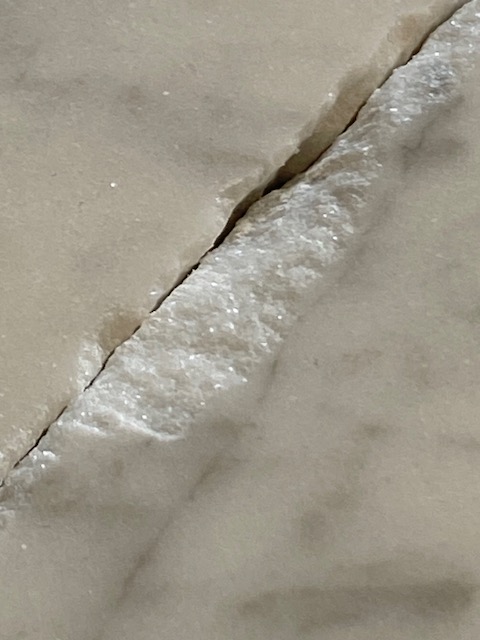

Michelangelo described the process of creating his magnificent sculptures as a matter of seeing the form within the marble and then removing everything that didn’t belong. With this lens on the process, Michelangelo didn’t so much create David as reveal him by chiseling away the block in which he was encased.

Michelangelo placed his talent in service to the image he was given. Through his inner vision he engaged with a reality not yet manifest in physical form. He gave it his attention, recognized its value, and worked to bring that vision into the material world. The profound beauty of the sculptures he created gives credence to his way of working.

Our more ordinary creations may not reach the stature of Michelangelo’s David, but being guided by the end product that we envision makes bringing something new into the world—writing, teaching, decorating, cooking, or any other creative endeavor—feels a little more manageable. A guiding vision makes it easier to recognize what does not belong, and to chip it away.

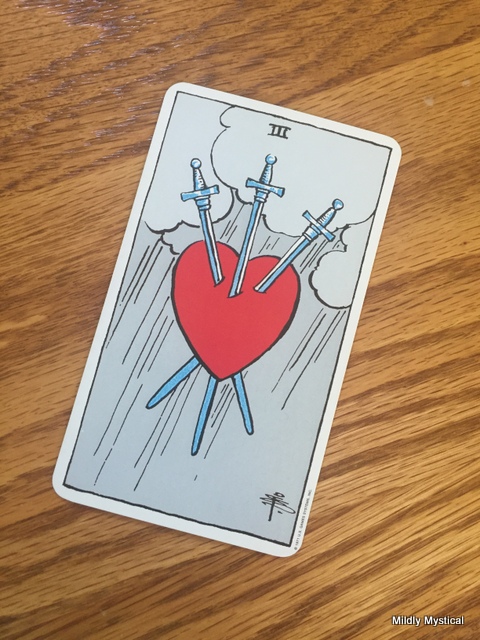

In the King Arthur legends, the sword of kingship is encased in stone, and only the true king can draw it out. In these stories, what lies embedded in the stone is a true identity, revealed not by chipping away the stone but by extracting the sword. That is another way of describing the challenge for each of us—finding the connection to our own true heart and our own true calling so that we can claim and wield the sword of our unique power and agency.

Like Michelangelo’s freeing of the form within the marble, the symbolism of extracting the sword points to a way of freeing the essential beauty of our soul. Our potential, our creativity, our ability to love, often lies hidden within the hard stone that we’ve learned to use for protection. As life unfolds, we find out more about who we really are and learn to let go of the things that get in the way. In the process, we bring our long-obscured form into the light.

It would be great to have a clear vision of that final form, but that is not clear to me. Nonetheless, I am getting clearer on the patterns that do not serve me, and I’m working on letting them go. In that way, I’m chipping away at what doesn’t belong.

Through it all, I trust that there is some higher wisdom, a knowing that is not fully conscious but which urges us in the direction of wholeness. I try to stay attuned to this lifegiving movement, known by many names: the Higher Self, the Higher Mind, the Divine Wisdom, the Light, the Truth, the Ground of Being, the North Star, Divine Guidance, the Life Force, the Tao, God.

Whatever we call it, I believe that this loving and life-affirming presence does see the essential form that’s possible for each of us. It offers us guidance and direction for chiseling away what does not serve, and setting free what is encased in stone.

Susan Christerson Brown