Earlier this week I took an evening walk under a canopy of beautiful old trees. The light was golden, shining through the sheltering limbs. But as the breeze stirred, the walnut trees did what they do in the fall. Suddenly I was surrounded by the force of heavy green-husked globes pelting the pavement and splitting open. Hoping to avoid a knock on the head, I scurried to the other side of the street.

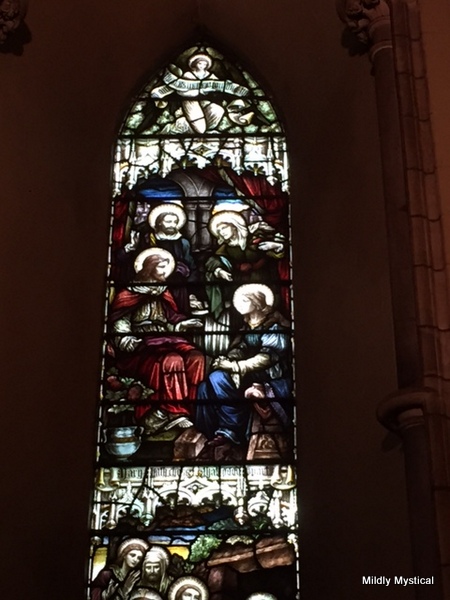

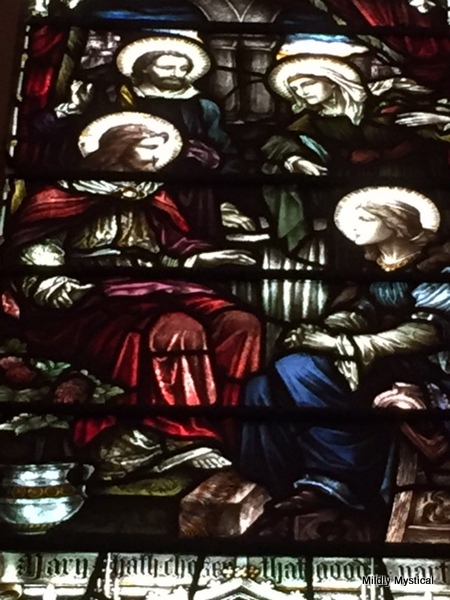

Last week on a retreat at Loretto, I also found walnuts wholly or partially encased in their hulls scattered across the grounds and walkways. I had to watch where I stepped to avoid stumbling. These gifts from the trees can trip you up, but at the same time they offer themselves to whomever will gather them.

The retreat was led by Lisa Maas, whose ability to lead Spirit-centered groups has enriched my life again and again. Over the two days we spent together, our group talked about the fears and self-protective habits that get in the way of fully experiencing life, love, other people, and the presence of the Divine. Using the tools of the Enneagram, we looked at our personal types according to our primary coping strategies. We considered how, though they may have served us well long ago, those patterns of behavior eventually interfere with living a full life.

Coming face-to-face with how we limit ourselves through long-held patterns is a moment of truth that can be very painful. Yet that is the human condition, and seeing it is how we come to maturity. The path to our transformation is through our weakest aspects. In our encounter with the inadequacy of our approach to life, we invite the divine healing that turns our limitations inside-out and reveals the gifts, and the strengths, that are uniquely ours to share with the world.

I was thinking of all these things as I walked the campus of Loretto. I considered gathering the walnuts lying about, but that black inner hull meant unavoidably staining my hands and clothing. I love walnuts, but there is no way to get to them without encountering the messy blackness surrounding the nut. On the other hand, the intact hull is beautiful, and bowl of those green spheres would make a lovely display. But what a waste it would be to never get to the real treasure inside.

I’m glad to find walnuts at the grocery store already hulled and shelled. But in our authentic spiritual lives we are not spared the messiness. The way to spiritual maturity leads through dismaying truths we don’t want to contend with. But this is simply how growth works. If we can bear to be present with them, our shortcomings show us what we need. They break open our husk and reveal our vulnerability, our need for guidance, and the way forward.

That’s how we get to the heart of life. That’s how we grow into who we really are. Our frailties make us part of humanity and teach us compassion—for ourselves and others. As Leonard Cohen says, “There’s a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.”

Looking deeply at what is can be messy, like a walnut hull’s black interior. But that’s not the end of the story. If we keep going we find what is nourishing and delicious. We’re surrounded with reminders and invitations to take this journey. Walnuts are falling all the time, trying to get our attention.

Look out!