I keep thinking about an article I read from the Atlantic recently, “Alcohol as Escape from Perfectionism” by Ann Dowsett Johnston. Its poignancy comes from Johnston’s ability to put her finger exactly on the place where the determination to live up to an impossible ideal leaves us vulnerable. Intellectually, I know that unreasonable expectations are unhealthy, but I didn’t expect to be so deeply touched by the place in life she describes.

My children are young adults now, and I have grown since they were children. But as if it were a coat hanging in my closet, I can still wear the sense of responsibility from those years, and I can easily wrap myself once again in a state of mind that said I was never doing enough, or doing it well enough.

I thought there was a right answer for how life should be lived, and my job was to reach that answer, claim it, and make it work. That applied to having a family, making a home, serving the community, and somehow finding my own work. There were standards for living a good life, a worthwhile life. They had to be met. I couldn’t have told you that’s what I believed, but it was the water I was swimming in. There were things I was supposed to do. Whatever it took, I had to find a way to accomplish them all. Except, of course, it wasn’t possible.

Measured by the distance from where I thought I should be, my life fell short. I fell short. All I could see was the gap, what wasn’t done, what I hadn’t achieved, where I hadn’t reached.

Where did that come from, that certainty about what I was not? The dismissiveness about what I was? Who pointed to that place out of reach and said that was where I should be? Who insisted that nothing else mattered as much? I don’t know why I was so unkind to myself.

As a young mother, Johnston would sip wine to ease her transition from the day at work to the evening and its responsibilities at home. It was a pleasant ritual, then it became a necessary one. She wouldn’t give herself a break on what she expected of herself, but she would pour herself some wine. Genuine self-care wasn’t part of her world, but she kept wine in the fridge. Until little by little, the wine took over.

I didn’t rely on wine, but I nonetheless recognize the state of the soul that Johnston describes—the refusal of compassion for oneself. I turned my back on myself and accepted what the world said: Just get it done. All of it.

I wish I could have told my younger self that I was good enough, that my needs mattered, that kindness to myself was not the same as self-indulgence. But perhaps I can pass that message along to someone else who needs to hear it.

It doesn’t always come naturally to show ourselves the kindness we would offer to a good friend, but there are good resources that help. My thanks to Lisa Gammel Maas for pointing out the work of Kristin Neff on self-compassion.

May you be well.

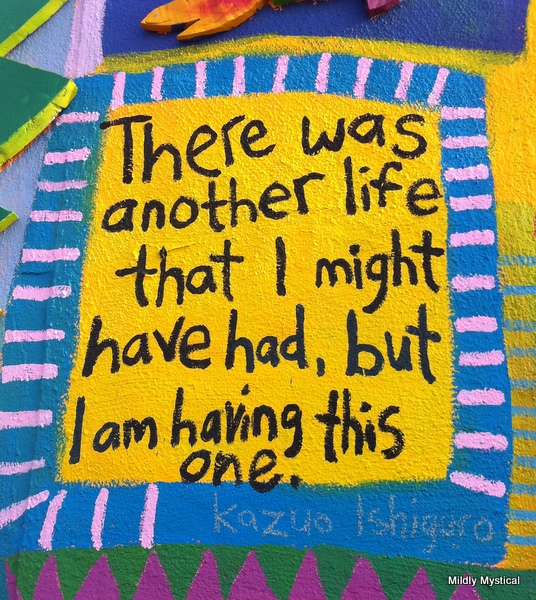

* The wonderful artwork above is by the inimitable Pat Gerhard, and is found on the wall of the warm and welcoming Third Street Stuff and Cafe in Lexington.

Thank you for this post, Susan. You capture my memory of those mothering years. I could feel how relentlessly I drove myself, but could find no way to “turn off.” It was writing that finally came to my rescue and allowed me to justify the stillness it took to discover what I was thinking and feeling and to put it down on the page. The act of attention that writing required gave me respite from constant “doing” and never feeling I was doing enough (or well enough).

I will share this post with my daughters and friends.