Lately I’ve been learning about creating sacred space and leading worship for young children. Familiar rituals, an unhurried presence and clear focus, quiet voices, a space arranged in an orderly way, and a tranquil and consistent way of doing things—all of these are part of infusing the space with a sense of sacredness. The insight of thoughtful people who understand both children and worship has me thinking about the connection between a sense of order and sacred space, not only for children but for adults as well.

Our world is messy and the days bring disorder of various kinds. Interactions between people go awry; the systems that should facilitate our lives often put up roadblocks instead. Our bodies, our plans, and the myriad details we juggle are all subject to breaking down. In ways both large and small, we are continually reminded that life is out of our control.

Especially when life feels chaotic, we need to find a sense of order somewhere. Within ourselves, if nowhere else, we need a sense of stillness and peace to move through the day with any grace at all. Nature can be a refuge, but we also need beautiful and tranquil spaces indoors, sheltered from the elements. From the most exalted to the most humble, the sanctuaries we create offer a place apart from the disordered world. We hope they will be infused with meaning, order, and beauty. When done well they embody sacredness beyond any particular beliefs associated with them.

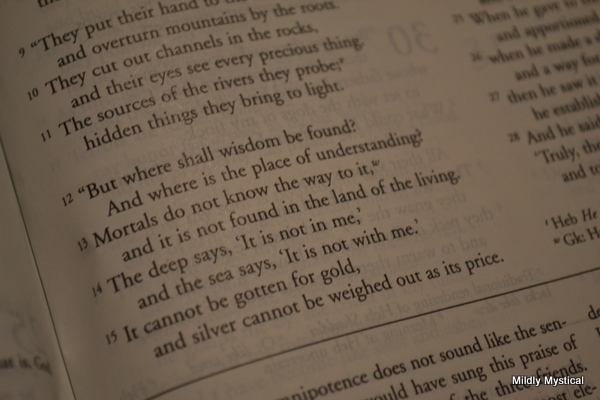

A sanctuary with meaningful rituals offers a place and time for finding order in the midst of confusion. It creates a clearing where we can regain perspective, remember our priorities, and pull ourselves together to face whatever comes next. Sometimes we encounter the divine, other times the reassurance of a familiar practice is enough.

But in either case our impulse to seek order and ritual, and to find in it a connection to a higher order, puts us in touch with the holy. Our instinct to create sacred space is itself a divine gift. Whether or not we feel we’ve encountered God, the sense of finding order and tranquility is restorative. It helps us to act more effectively, live more compassionately, and appreciate life more fully.

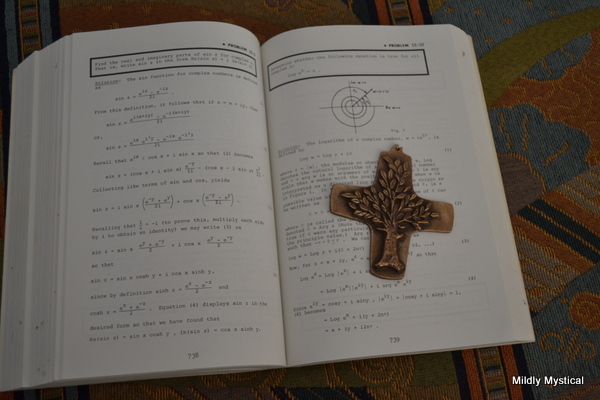

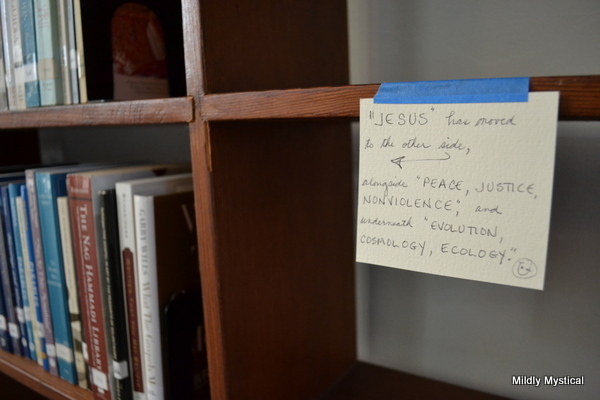

Of course order alone doesn’t make a space sacred. A shallow kind of order can be imposed on all kinds of spaces, and preoccupation with order can crowd out vitality and creativity. There’s nothing sacred about oppression or stagnation. Faith communities and their places of worship can be a rich source of ordering one’s life and clearing the way for growth, or they can impose world views that are stifling and limiting.

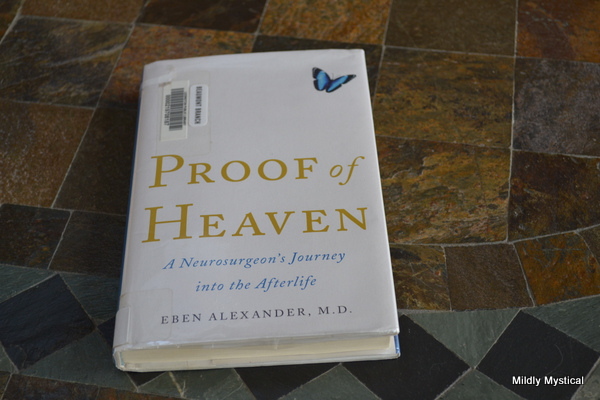

Jesus said, “My yoke is easy and my burden is light,” but so many oppressive claims are made in the name of Christian religion that many folks have given up on Christianity and on religion in general. That’s unfortunate, not only because many Christian communities are loving and inclusive, but because few other places are prepared to offer the sacred spaces and rituals that human beings need. People at all stages of life need somewhere to find order and tranquility. Are there places outside of religious communities to offer it?

Where do you find sacred space? What helps you to sort things out and find a sense of order and peace?