A rich conversation a few weeks ago has me thinking about how often the Bible is abandoned in the pew when people leave the church. It’s like a painted masterpiece hidden behind a forgettable print. Lots of folks equate the Bible and the church, but they are not identical.

The scriptures collected in the Bible have spoken to people for thousands of years, even as each generation decides for themselves whether those writings continue to have value. It’s fair to ask whether the Bible has anything real and relevant to offer. The question is as old as the scriptures, and asking it keeps the Bible alive.

Exploring the question of whether scripture matters becomes easier when we become aware of the smudged lens we’re looking through. There are all kinds of assumptions and agendas we might have inherited for reading the Bible, ideas that we might want to question.

For example, we might have gotten the idea that the Bible is more or less a book of rules. But the many stories of dysfunctional families told in scripture is enough to counter that mistaken notion. The Bible isn’t a single treatise, it’s a library of books in conversation with one another.

Neither is the Bible intended to be a literal account of historical facts. The biblical writers were concerned with something much more important to the heart of life than recording particular events; they were interested in the meaning of how life unfolds.

If we learn these stories as children, we appropriately absorb their symbolic power in a naïve and literal way, touched by the story but not yet cognizant of the difference between literal and metaphorical truth. This is part of the beauty of childhood, and the delight of seeing the world through the eyes of a child.

For example, the story of Jonah contains a scene where Jonah is swallowed by a big fish—amazing! Little ones have no need to question whether this is literally possible. They identify with Jonah, knowing how it feels to be overtaken by what we cannot control and taken where we don’t want to go. It can be scary! Jonah wants to run away from God, and finds out he can’t. Yet in this story things turn out ok, and a child finds reassurance in that. Even in the frightening parts of the story, God takes care of Jonah. What a relief!

As we grow into adulthood we need more subtle levels of engagement if the story is to continue speaking to us. The child’s understanding isn’t wrong, but there is more to explore. As adults we can learn to consider the story from a symbolic perspective.

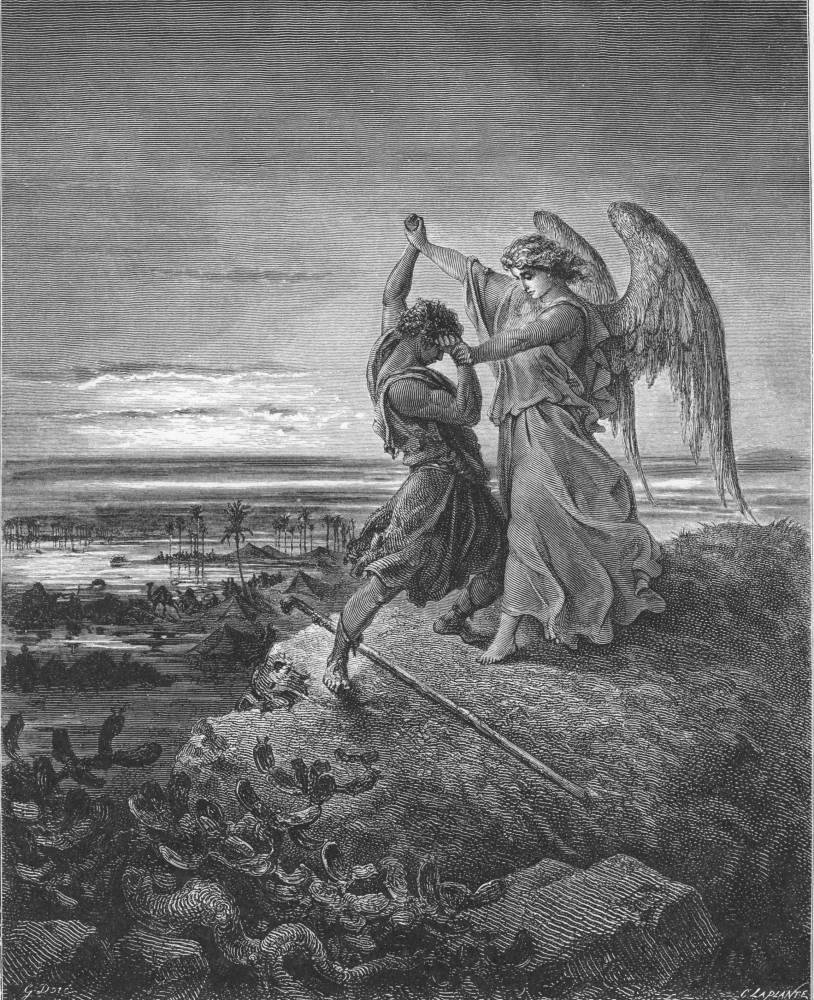

When Jonah tries to avoid what he needs to do, his life is churned up like a storm at sea. We know how scary that chaotic state can feel. Unless he faces the issues that lurk beneath the surface of his consciousness, Jonah and those around him are in danger. Resisting what life requires of him leads to nothing but trouble. When Jonah finally acknowledges his powerlessness over his situation, yielding to what feels like certain death as he stops resisting, it’s like being thrown into a churning sea. But instead of perishing he finds himself caught and held by an immense power. He relinquishes control to a mysterious force and finds it not threatening but life-saving. It takes him where he needs to go. Amazing! By submitting to a wisdom and will greater than his own, Jonah’s life is saved. As is ours. When we can release our ego’s grip on its own agenda, life will support us in ways we could not anticipate. What a relief!

If we cannot enter the symbolic meaning of what the Bible offers, we cannot fully enter into its depth and power. But we need support in learning to view the biblical writings in a fuller and more nuanced way. Without that support it’s no wonder people reject the stories as nothing but relics from childhood.

Looking at the Bible with a fresh lens brings the writings to life, whether inside or outside of church. No church holds the definitive interpretation of scripture. In fact, the Bible’s stories and teachings grow in meaning when they are lifted out of old contexts and into new circumstances, read with the lens of new experiences. We can take the Bible into the places where we find ourselves, whether or not we expect to find the church there.

Scripture is portable and always has been. It travels into new environments in a way that a particular church, which exists in a particular place and time, cannot. For better or worse, that’s why we have so many different churches and denominations. People read the Bible and bring their own interpretation to it. They see something new and want to build a community that approaches life in a new way.

Its portability has also allowed scripture and those who value it to endure massive upheaval. When the First Temple in Jerusalem was long ago destroyed and Israel sent into exile, they recorded the stories that sustained them, becoming people of the book. After the destruction of the Second Temple, when its centralized religious practice ended, the scattered nation endured by relying on what individuals could take with them: private rituals, prayer, and scripture.

Buildings and institutions come and go, but the issues wrestled with in scripture endure. The writings deal with archetypal forces that impact human life, a full range of emotion and experience. The deep history of these ancient writings speak to the deep reaches of human experience. The stories explore everything from humanity’s struggle with power to the call of what our soul longs for most. They’re as relevant today as they ever were.

In the next few weeks I’ll be mulling over some of the stories I love from the Bible, and sharing brief reflections on them here. Whether or not these stories are familiar, I invite you to see them anew and hope you’ll find in them some connection with your own journey.

Susan Christerson Brown