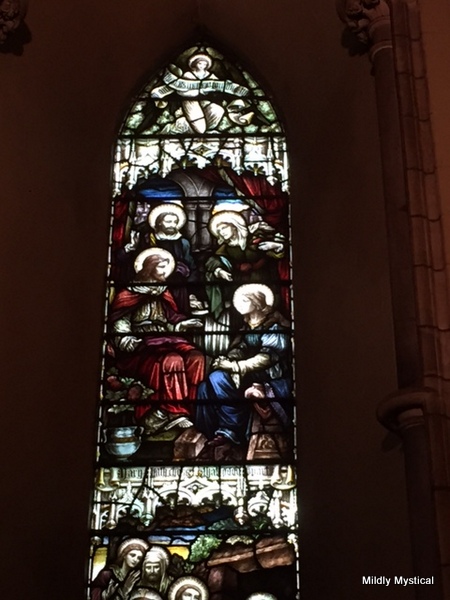

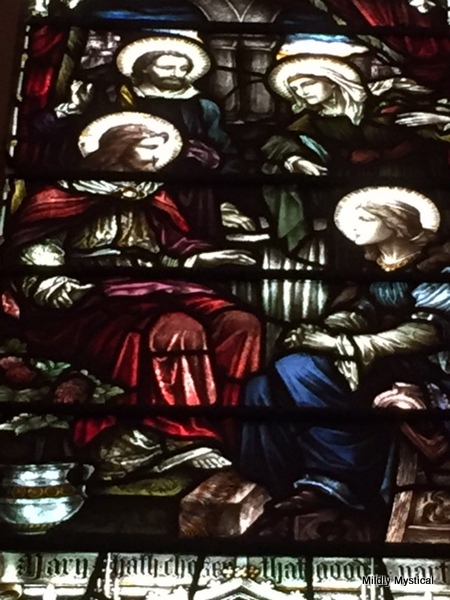

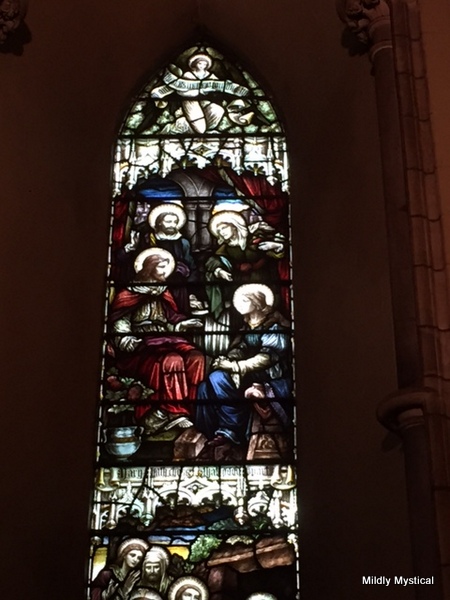

I have long wrestled with the story of Mary and Martha* in the gospel of Luke. In my reading, Martha is a worker; Mary is a listener. Martha is active; Mary is contemplative. As the two sisters host Jesus in their home, Martha is busy with the tasks of running a household while Mary sits at Jesus’ feet absorbing his teaching. Martha is angry about doing all the work herself, and insists that Jesus have Mary help out with the chores.

I understand Martha. It takes work to keep a household or anything else running smoothly. Martha wants to offer the finest hospitality to this amazing teacher. Perhaps she would have liked to sit and listen, but it takes work to provide a clean bed and a good meal.

Jesus responds by speaking kindly to her, noticing that she is worried by many things, and offering a different perspective. He points out that the work she thinks is necessary is actually distracting her from what is most important. Whatever standard Martha is trying to meet, it isn’t set by Jesus. He wants her to know that she is made for more than the treadmill she has put herself on. Jesus didn’t show up just to add to her chores.

I understand Mary. She is drawn to the wisdom of this new teacher and the power of his presence. She sets aside her normal activities, recognizing that this is no ordinary guest, and gives him her full attention. Yet following her heart means not living up to others’ expectations for what she should be doing. It’s not easy to disappoint Martha, who doesn’t share Mary’s priorities, and lets Mary know that she’s not doing her part.

I have long wished the story would show Jesus inviting Martha to sit down and listen, then have everyone pitch in with the chores.

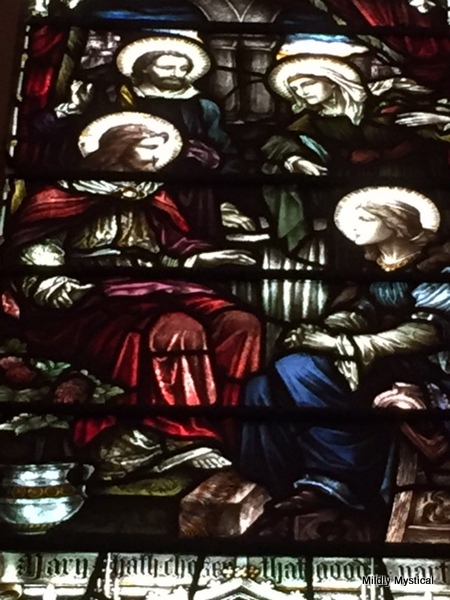

We all have mundane tasks to do. But it’s important to recognize what merits setting them aside. Jesus refuses to send Mary back to her usual tasks just as she is beginning to hear his life-changing teaching. Mary has chosen the better part, he tells Martha. Jesus doesn’t want us doing more chores, he wants us to be transformed.

Mary and Martha both live inside me. There’s nothing wrong with Martha wanting to get the job done. The world is in need of a great deal of work. But the world needs Martha to lend her strength and skill to the most important tasks. In a world of “shoulds,” how to discern what truly is the better part is a question always before us. We need Mary and her ability to recognize what is genuinely life-giving.

Carl Jung offers an insight regarding his patients’ growth that applies to the tension between Mary and Martha:

All the greatest and most important problems of life are fundamentally insoluble . . . They can never be solved, but only outgrown. This “outgrowing” proved on further investigation to require a new level of consciousness. Some higher or wider interest appeared on the patient’s horizon, and through this broadening of his or her outlook the insoluble problem lost its urgency. It was not solved logically in its own terms but faded when confronted with a new and stronger life urge. (as quoted by Matthew Fox in Original Blessing)

We need both Mary and Martha, not in opposition but in a complementary partnership. We need a higher level of awareness that incorporates them both. I like to think of Martha spinning a cocoon, Mary yielding to the transformation that happens within it, and through the work of the Spirit, a new creation emerging into the world.

*The text of the story is brief, found in Luke 10:38-42. Here it is, in its entirety:

Now as they went on their way, [Jesus] entered a certain village, where a woman named Martha welcomed him into her home. She had a sister named Mary, who sat at the Lord’s feet and listened to what he was saying. But Martha was distracted by her many tasks; so she came to him and asked, “Lord, do you not care that my sister has left me to do all the work by myself? Tell her then to help me.” But the Lord answered her, “Martha, Martha, you are worried and distracted by many things; there is need of only one thing. Mary has chosen the better part, which will not be taken away from her.”