Over the past few weeks I’ve been immersed in The Artist’s Way, leading a group in the shared experience of reconnecting with our creative lives. Each week brings a different focus, but in general we practice making space in our days for things that bring true joy and delight. We learn, or relearn, to trust those sparks of life. They are the source of divine encouragement and inspiration.

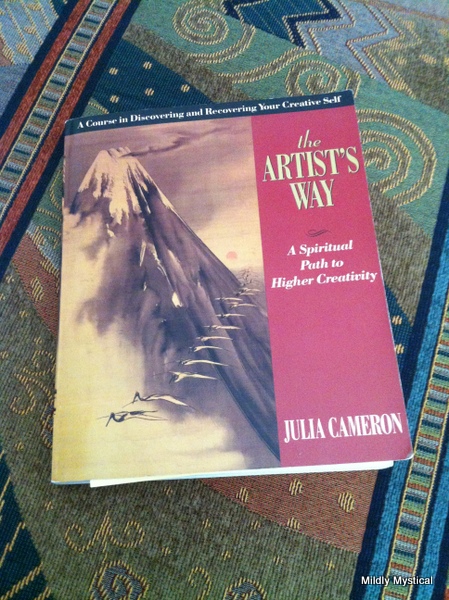

The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron is presented as a program for people blocked in their creative work, but it is actually a spiritual practice that enhances the life and the work of anyone who wants to live more fully. It offers a way of recovering the “something more” that we long for, which empowers us to bring creativity to our lives in all kinds of ways. It helps us open to new possibilities rather than remain in the constricted space that we long ago decided was safe.

In the sixteenth century Ignatius of Loyola developed The Spiritual Exercises, which the Jesuits (the order to which Pope Francis belongs) have used since then as a guide for spiritual formation. The exercises are grounded in the gospel stories, and are undertaken by those seeking a meaningful and even transformative spiritual experience. They can be the focus of an intense thirty-day retreat, or worked through by setting aside regular time in everyday life for a few weeks. If you’re interested in a simple version of the exercises, an excellent book is Moment by Moment: A Retreat in Everyday Life by Carol Ann Smith, SHCJ and Eugene FR. Merz, SJ.

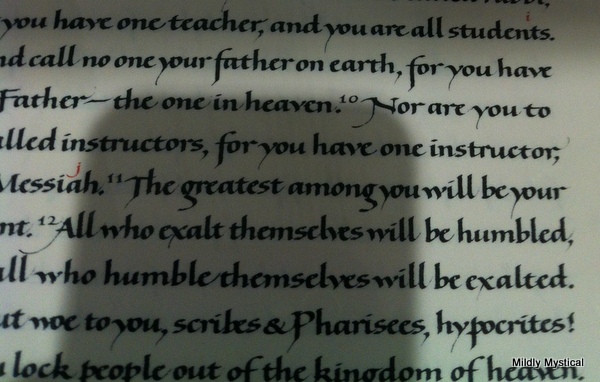

I have come to see The Artist’s Way as a practice of comparable value. It marks the trail of an authentic spiritual journey, tailored for the culture in which we live. It is not a specifically Christian path, though it makes reference to ideas and occasionally quotations from the gospels. It is very much a God-centered path, inviting us to think of God and to find God in new ways. Working through the twelve weeks of The Artist’s Way is a transformative experience for many people, both within and outside of the church.

The readings and practices create an opening for the Spirit. The discipline of The Artist’s Way helps clear away the debris that covers over the clear spring of our creativity. We open ourselves to the flow of life, of energy, of creativity, of delight, of hope, of optimism, of generosity, of abundance, through taking on some simple practices. We gain a better sense of the spiritual path and the creative work that we are uniquely called to. We allow what is most essential, most alive, most truly ourselves, to find an outlet in our lives.

But don’t take my word for it. Try it. Write out your answers to the questions this book poses. Take on the practices of morning pages and artist dates. See what happens. You don’t have to buy into new beliefs or set aside old ones—although you might find yourself considering new ideas. For an investment of thirty minutes to an hour a day to work through a chapter a week, you might find your life infused with new energy.

In my experience, and that of many others, The Artist’s Way can be an opening to the creative Spirit that hovers over the waters of Genesis. Its practices blow gently on the ember of the divine in each of us, and helps rekindle the creative fire at the heart of a life fully lived. Right now our group is finishing up Week 6, and I’m excited to see what emerges in the second half of the journey.