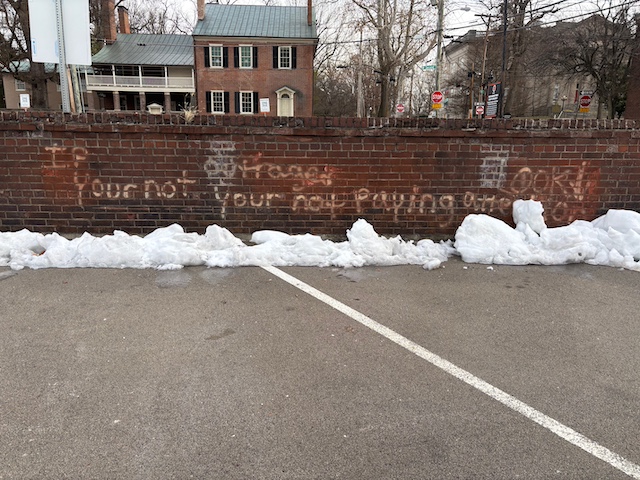

On Sunday morning I photographed this line of graffiti, painted along a long, low brick wall: If you’re not outraged, you’re not paying attention. Along with the directive: LOOK

I could feel the anger and frustration behind the words, the desire to pierce the bubble of those who are comfortable and complacent. It’s a sentence, written at the scale of whole-arm movement behind a can of spray paint, with the power to hook me.

I don’t want to be guilty of not paying attention. Attention matters. And attending to what matters is a moral duty. Closing ourselves off from the world is not what we’re here for. Yet neither are we here to live in a state of outrage. It exhausts us, while serving no good purpose.

How can we pay attention, yet not live in a continual state of outrage?

It helps to notice that eliciting outrage is often a form of manipulation. Those who want our outrage want to control our attention and our energy.

One form of this manipulation is through taking action that provokes outrage. This is a way of both directing and thwarting our attention, like a magician gesturing grandly with one hand while performing a sleight-of-hand with the other. To understand what’s really going on, it’s important to look at more than what is being overtly presented.

Another kind of manipulation is using outrage to gather a following and fuel a movement. This kind of manipulation is more subtle. It uses righteous indignation, which can seem like the high moral ground. This is tricky territory, because the flare of anger can indeed bring with it energy for important action. Anger brings with it information about a line that has been crossed, and the energy to respond—hopefully with clarity and respect for life. Anger in itself, when it moves through and moves on, is not a problem.

Remaining in a state of outrage, however, steeps us in a toxic brew. It limits how we see the world; it impedes the growth of creative solutions to problems. Overtaken by outrage, we lose the ability to discern when our efforts are no longer effective. Living from a place of outrage turns the world into a battlefront that gives life to no one. It cuts us off from the source of life, and from one another, as we rely only on our own rapidly depleting resources. We become brittle, like the dying branch of a tree.

When we can pay attention and respond from a place not rooted in anger, but in the fertile soil of wisdom, then we have something to offer that actually makes the world better. When we can set aside our own reactivity, and allow our actions to be led by what is highest and best within us, we have a chance to bring healing to ourselves and others. We can only do this if we can consciously choose where to place our attention.

Where there is life there is hope. The brittle branch may yet show a green bud in the spring. Our rough bark can still hold the life force that unfurls a new leaf.

What new life might we be a conduit for?

Susan Christerson Brown