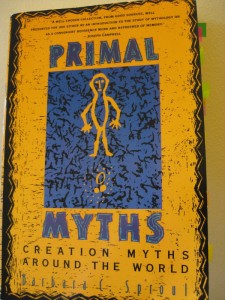

Lately I’ve been reading Barbara C. Sproul’s Primal Myths, and enjoying her insight into creation stories from around the world. As she explains in her introduction, creation stories offer a glimpse of the infinite and unknowable by showing how that absolute reality permeates the world we know. The stories are concerned with the world we experience and its connection to the ground of all being, which lies beyond our experience. Creation myths express the spiritual truth that “the Holy is here as well as everywhere; it is now as well as always….The Holy is immanent as well as transcendent.”

There are many stories of beginnings, but I love those that show the world created out of the chaos that precedes all existence. The creator, standing outside of the categories of being and not-being, encounters a primordial sea of pure potential. From the abyss of unrealized possibilities the creator speaks a word, gives definition to an idea, and confers upon it existence. The creator fashions what has never been from the chaos of all that might be.

Sproul makes an interesting distinction between two kinds of chaos, one full of potential and the other a force for tearing down. A generative expression of chaos is very different from the forces of chaos that threaten to destroy. In Sproul’s words, the chaos that precedes creation “is a fruitful pre-order rather than a negative dis-order.” They’re probably related, but that’s another post.

The chaotic sea of potential is not something to resist; lingering there expands possibilities and allows a new vision to emerge. If we want to do something different from what we’ve done before, we can’t insist on putting thoughts and plans in order too quickly.

At the same time, to thrive we need structure that promotes health and well-being. We need enough order to support our basic needs, so that our attention can be freed to pursue what feeds the soul. A fruitful pre-order is necessary for creative work, but the chaos of disorder gets in the way.

I like to write early in the morning, before I do anything else. It’s a small-scale dip into the primordial chaos, when words carry news from another realm. I do that knowing that when I’m ready I can start the coffee brewing, turn on the computer, get breakfast, a shower, clean clothes, and move into the day.

But in the midst of my early-morning writing today, the power went out. No coffee. No internet. No hairdryer. No light in the bathroom. It made the morning a new challenge, requisitioning more attention than the usual routine requires. I set aside my work early to contend with the changed circumstances.

In a small way, this is an example of how disorder leaches energy from creative work. Establishing the rudiments of life requires effort in the best of circumstances, but without some kind of structure for support it’s hard to do more than get the basics covered.

There’s a limit to what I can control, and there’s only so much I can reasonably (or willingly) do to make life orderly. But I’m working to keep the distinction clear between the pre-order I need to encounter and the disorder that works against me.

What kind of relationship do you have with chaos?