I would love to be looking forward into the new year with energy and clarity. It would be great to be moving ahead, powered by a sense of direction and a spirit of taking charge. But what I’m feeling is that I’m behind already.

Over the holidays it felt wonderful to check out from the news and the routines and even the Zoom connections that carried me through the prior months. Resting from them makes clear the effort that they all require. Now the gears are creaking as I try to get going again.

Transitions are hard for toddlers, and maybe they don’t really get any easier. We simply learn to soldier on. With the new year underway, it’s time for plans and schedules. The unopened door into the work that I have yet to begin is daunting as always. I have to remind myself that the work most always ends up being do-able once I walk through that door. It’s just a matter of turning the knob and leaning in.

Like all of us, my particular circumstances are set against our larger societal challenges. Bearing up in the current climate requires some effort in itself. There’s a race out there between the vaccine distribution channels and the new, more contagious, strain of coronavirus. I had internalized what felt ok to do, the volume of traffic in a store that felt safe to enter. Not much felt ok. Now the level of contagion is worse and I no longer have that sense of what’s safe. The virus is moving faster and the vaccine seems to be rolling out in slow motion, getting no closer to me at all. It’s a terrible thing when trying to live with good, responsible judgment seems indistinguishable from living in fear. And now there’s the chaos in Washington, too.

For weeks I’ve held onto how Rabbi Ari Saks recently described the meaning of Hanukkah. It speaks directly to this time. He says that lighting the menorah celebrates a victory in the midst of a larger battle, the outcome of which is yet unknown. It’s an act of faith, a way of drawing strength and courage from the small sources of light along our path. It’s also an act of courage to name what we hope for, to tend it, and to work for it.

That’s where we are as this year begins. There is hope and good news, but the shot in the arm is not here yet. There’s a new vision and leadership, but the transfer hasn’t happened. We’re in between the promise and the manifestation, and we persevere.

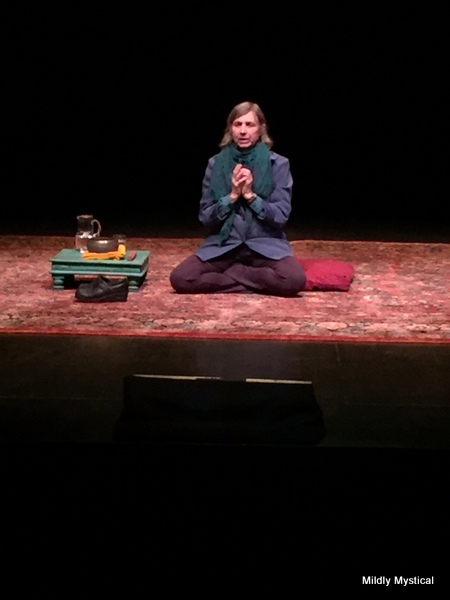

Once a week I tune in for a guided meditation offered by a wise teacher named Marion Gilbert. During her Monday Meditations I experience my burdens being lifted. It shifts my perception in a way that lets me feel absolutely carried and supported, with a perspective that allows me to be completely at peace. It works on my psyche just like smoothing an animal’s fur.

My worrying mind wants to be in charge. It thinks it should be in charge, yet has no capacity to change much of anything. My strongest agency comes from where I place my attention and what I choose. The best choice is to find that solid place to stand where I can observe the mind doing what it does, and be aware all the while that reality is bigger than what the worrying mind is able to perceive. That’s when I can remember that I’m being carried into the new year, that it’s not all up to me, and that ultimately all will be well.

Peace be with you.