This week I cleaned up the garden bed, neglected since last fall when I managed only to stack the tomato cages and drag away the spent vines. The winter’s brief deep freeze took the rosemary, leaving a dry and brittle carcass to dig out of the ground. The newly green thyme and mint looked healthy, and I was careful to work around it. I pulled fragrant wild onion, hoed up violets and clover, raked out and removed grasses and vines. With an entire bed of turned soil exposed to the sun, a new wave of weedlings will no doubt sprout soon.

It can be a pleasure to work in the spring garden, but something cast a shadow over that effort. Even as I was accomplishing what needed to be done, I noticed the familiar voice of my inner critic. The critic didn’t give me credit for the work I was doing. Instead, it kept pointing out that I should have accomplished this task months ago.

Just like the untended garden bed, the soil of my psyche yields its own unwelcome perennials. There is always an interior voice, critical and judgmental, that insists I should do more and be better. I’ve learned that what needs tending, just like a garden bed, is my inner landscape with its unrelenting inner critic. That’s who was judging me for being late to the task.

That inner critic would easily drain all the joy and satisfaction out of accomplishing the job, if I allowed it. The inner critic has no capacity to enjoy the day or to celebrate what has been completed. It can see only that the work should have been done already, and that there is more to do. In matters large and small, the critical inner voice is capable of acknowledging only the ways we fall short.

If we’re fortunate, at some point we realize that the inner critic does not know how to embrace life. It insists we work harder to be good enough, but never allows us to claim that blessed state. The demands of the inner critic are discouraging, not life-giving. It’s not helpful to chastise myself even as I’m working on what needs tending—whether it’s my garden or my life. If that’s how it has to be, no wonder I put off getting started.

There is much left to do in the yard, chores that might have been done a month ago if I had spent more time at home or worked a little harder when I was. But I want my work outdoors in the Kentucky springtime to be a pleasure as I pull weeds and set new plants. To have any chance of enjoying the garden, I need to be ready for that critical voice.

I’ll probably never be rid of it, but I don’t have to let that voice take charge. I can invite the inner critic to sit on the ground next to me. After all, she truly believes that she’s helping me to be good, to be worthy, to be safe from the criticism of others, and deserving of a place to belong. She believes it’s all up to her to see that I earn my place in the world. She has helped me to accomplish many things, but she can’t take in the beauty of life just as it is. She can’t experience love because she’s so busy trying to be worthy of it.

Whether tending a garden or tending the soul, it’s necessary to pay attention to what’s coming up. Weeding and cultivating both our inner and outer lives teaches us about ourselves and about the world. It creates a space where goodness can grow and flourish. It brings healing and abundance, allowing us to live more fully and become more whole.

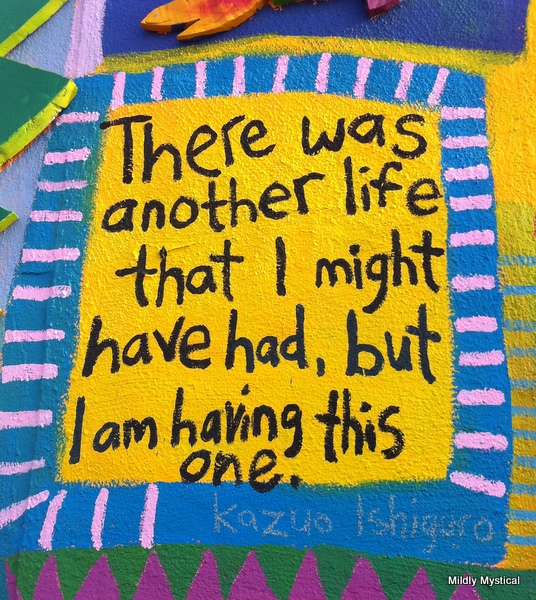

As we learn to pay attention in this way, we begin to see more clearly. We’re better able to respond with what is needed. Of course, this takes time. It happens slowly as our lives unfold. It doesn’t mean we’re late. There is nothing to be gained from berating ourselves for not having come to it sooner.

Jesus offered a parable (Matthew 20:1-16) in which the workers who showed up to the vineyard late in the day were paid the same as those who had labored since morning. The same pay, whether for eight hours or for one? It doesn’t make sense. The part of me that tries hard to do right and wants the reward I’ve earned stands with those in the story who worked all day. “That’s not fair!” they protest, and I see their point.

But the point of the story is not that we are hard workers being taken advantage of. Rather, we are the ones showing up late in the day. It takes most of us a long time to arrive at the beautiful truth of who we are and what life is about. The part of me that feels aggrieved by how the workers are paid is aligned with the inner critic, passing judgment for being late—whether in getting a task done or in cultivating the life of the spirit.

Most of us show up for spiritual work when much of the day is spent, and Jesus taught that we’re not late. Making space for something beautiful and life-giving to grow from our little plot of earth is something to celebrate, no matter when it happens. We are welcomed and rewarded with fullness of life whenever we arrive.

Susan Christerson Brown