Last week, workmen installed a new hardwood floor at our house. Preparing for that work looked a lot like moving—books packed away into boxes and furniture carried out. When the room was empty the old carpet looked even worse; this project was long overdue.

Two and a half days of noisy work followed: an electric saw wailing on the front walk, hammers pounding the planks into place, sporadic shots of a nail gun driven by a compressor that reverberated through the entire house. But in the midst of it all was the encouraging scent of fresh lumber and the satisfaction of seeing good work in progress.

After the oak was stained, the guys brushed the finishing coat over the wood, working their way toward the front door. They stepped backwards onto the porch, leaned in to close the door, and wished us well.

It was quiet. And beautiful.

An empty room with a glowing oak floor has a Zen-like tranquility. Waiting for the finish to dry meant it had to remain bare, and I enjoyed seeing this kind of space in the house. Later, even as I missed the comfort of the room’s furnishings, I was reluctant to move everything back in. The openness invites a sense of expansiveness, of possibility, that I didn’t want to give up.

Not allowing everything to return means making some decisions. It means sorting through shelves and baskets deciding on what’s worth keeping. And it means not letting things pile up once that paring down is done.

But I’ve been here before. And before that. It’s a cycle that continues. But in this case the change started at the foundation, and the decision is not what to carry out but what to bring in. Maybe that will make a difference. I keep having to learn over and over again that changing your space and changing your life seem to go together.

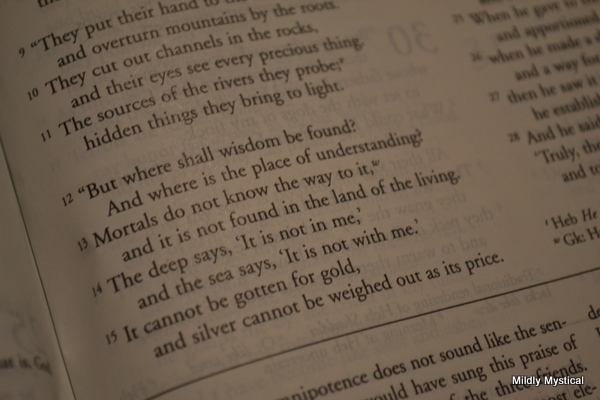

That expanse of uncluttered space, anchored by the warmth of natural wood, made me think of meditation. Maybe it seemed a perfect room for meditation because the open space, both restful and expansive, is like the mental and spiritual uncluttering that happens through meditation and prayer.

It’s also a physical embodiment of what the Sabbath is meant to be—an opening of time for what we value most, a space that allows some perspective on what’s most important. Sacred space and sacred time seem to be two sides of the same coin, and both help make room for the Spirit.

There’s a sense of renewal in transforming this room, just as meditation and prayer renew mind and spirit, as Sabbath renews the week. Creating it gives rise to the question of what is worth allowing into our space, and offers a reminder of how much choice we have in making that decision. It’s a practice worth repeating every week, or even every day.